When a Persian café in London reignited my love of Sindhi confectioneries

In today's newsletter, I explore the historical and culinary influences between Persia and Sindh through desserts. Don't read this on an empty stomach.

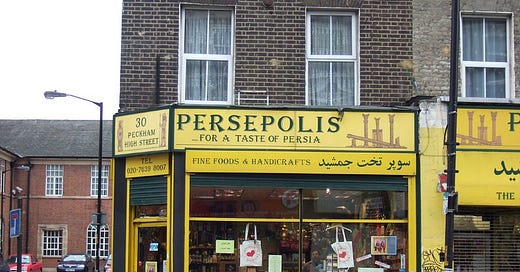

If you were to ask me if London is one of the best cities on Earth blessed with some of the most delicious food known to mankind, I’d reply with a polite no. Call it aftereffects of colonialism or capitalism, but the gleaming, shiny capital of England is often considered to be a gourmand’s favourite place on Earth. Not for this gourmand. In general, restaurants in London are massively overpriced with portion sizes of a baby’s shoe and the food is often lacking in basic flavour. But every once in a while, a restaurant or café would come along that would leave me speechless in its simple execution of flavoursome and wholesome food. An experience that is as spiritual as it is thrilling, I’d collect these restaurants in my mind’s eye like little gemstones that I would look back on fondly when my time in London would come to an end. I can still recall how their food brought time to a standstill in a very busy city. Today, I want to talk about one such London café in the southern borough of Peckham called Persepolis. When I walked into Persepolis, I had no idea on how its selection of nutty, buttery and sugary Persian sweets would remind me of Sindhi confectioneries.

A friend and I had journeyed to Persepolis in May 2023 from north London for dinner, but for the first time in my life, I wanted to skip to dessert. Much like an Indian confectionery shop, the Persian sweets were neatly stacked behind a glass pane with a weighing scale on top of the counter. Fresh containers of saffron rice pudding topped with pistachio flakes, crispy zoolbia dripping with a sugary saffron syrup and rows and rows of fudgy sesame brittle instantly transported me to my grandparent’s kitchen. This was the first time in London I’d felt remotely connected to my Sindhi identity beyond the Sindhi dishes I made in my London flat. It’s relatively easy to feel “Indian” in London as there’s already a thriving Indian community with Indian restaurants and grocery stores dotting almost every borough of the city. But feeling “Sindhi” seemed like it was twice removed for me, that is until I went to Persepolis.

Persepolis is run by an Iranian and British couple, Jamshid and Sally Butcher, who wanted to share a taste of Persia with London. The café is also a shopfront stocking preserved Iranian condiments, tinned cans full of beans and spinach, heady spices and dried herbs, loose packets of dried rose petals and pomegranate seeds, saffron stock cubes, dried fruits and nuts in transparent boxes, dates that are as big as small gherkins and Iranian rice cookers in all kinds of sizes. In hindsight, it was the combination of all of these that gave me a little glimpse of Sindh in London. This realisation was only reinforced last month when during the Indian festival of Holi, like most Sindhi families, we shared boxes of gheeyar, or zoolbia’s orange and tangier cousin. Where gheeyar is made of fermented batter, deep fried and then dipped in a saffron sugar syrup, zoolbia’s batter includes baking soda to allow it to rise quicker and is also dipped in a saffron sugar syrup. Zoolbia is often compared to the Indian jalebi, as is gheeyar but, in my opinion, gheeyar is a stronger reflection of Persia’s influence on India than jalebi which is usually smaller in size.

Sindh first came under Persian rule in 6th century BCE under Darius I within the wider Achaemenid Empire whose ceremonial capital was the city of Persepolis. It was around this time that spinach, saffron, pomegranates, almonds, pistachios and rosewater were brought to India by Persian rulers. Gheeyar is traditionally topped with dried rose petals and on occasion chopped pistachios or almonds, all ingredients that are still used to this day when preparing Persian sweets. Though zoolbia is devoid of these ornamental toppings, gheeyar is unmistakably of Persian origin. In one swift crunch, your palate is swept clean by the gentle flavour of rose petals as the tangy bits of gheeyar stick to your teeth and a sheen of saffron syrup coats your lips. In one swift crunch, you can taste 6th century BCE Persia on this bright orange disc.

The Persian bamieh, which is like a deep-fried churro dunked in saffron sugar syrup, is eerily similar to the Sindhi tosha, which is also a deep-fried oblong confectionery dipped in saffron sugar syrup. The consistence of bamieh is that of a choux pastry which is softer in mouthfeel than the consistency of Sindhi tosha which is usually denser. Yet somehow the two are connected by strands of saffron and a history that runs millennia deep.

Besides culinary influences, the other obvious Persian influence on Sindhi culture is the Perso-Arabic Sindhi script. In 8th century CE, Islam rulers invaded Sindh, and thereby other parts of India, and introduced elements of Arabic into Sindhi language. It wasn’t until the 16th century that Persia once again invaded Sindh under the rule of Nawab Shah, only to be replaced within 50 years by the Mughal invaders from Central Asia. Though the Mughals were reportedly from parts of Uzbekistan, they spoke Persian in courts and used Persian script for all official communication. It is likely that this double whammy influenced the Persian aspect of the Perso-Arabic Sindhi script. Before partition occurred, a lot of Sindhis also grew up learning how to speak Persian as it was easy for them to pick up on it due to its similarity to Sindhi. This script is, however, barely in use these days as a large chunk of the Sindhi diaspora is unaware of how to read or write this script. What a tremendous loss for future generations to not lose one, but two languages.

One underappreciated ingredient of Sindhi cuisine, with immense importance in Iranian culture, is dried pomegranate seeds. Pomegranates originated in the region surrounding present-day Iran and symbolise fertility and goodness in Iranian culture. While the symbolism of pomegranates within Sindhi culture is unexplored, it is an important pantry staple. A lot of older Sindhi cookbooks recommend using dried pomegranate seeds in the absence of tomatoes when cooking Sindhi recipes. Dried pomegranate seeds are added to the traditional Sindhi flatbread, called koki, to add a little bit of tang to an otherwise dense dough while fresh pomegranate seeds still find their way onto Sindhi street food. Mirchi pakoro is a Sindhi street food favourite where humungous chillies are deep fried after being dipped in a spicy chickpea flour batter. The crispy pakora is topped with luscious yogurt, a streak of green chutney and tamarind chutney with pearls of pomegranate scattered about. As you bite into the crispy pakora smothered in cooling yogurt, the burst of freshness from the pomegranate pearls relieves the richness and the spiciness of the dish.

I remember pomegranate pearls scattered about the mezze platter I had ordered with my friend at Persepolis. Soft pita bread was lathered with warm hummus and a side of oven-roasted dates drizzled in olive oil and sea salt. The pomegranate pearls shone like a constellation. Though I’d never interrogated the origins of my culinary heritage much when I was younger, in that moment in Persepolis, I wished I’d asked my grandparents more questions so that I could find some way to connect myself to the provenance of what was all around me. In that moment, I felt at home surrounded by the sounds and smells of a bustling Persian café but I lacked the context as to why. I am reminded of Panayiota Soutis’s article in Vittles where she talks about finding solace in a Turkish corner shop in East London while being of Greek-Cypriot heritage.

“I often feel homesick, nostalgic for a place I’ve never really known myself. But, wandering down the aisles of a Turkish supermarket in the middle of Hackney, I felt at home.” – Turkish Supermarkets: Treasure Troves in the Age of Corona

Eleven months after my visit to Persepolis, I am beginning to unravel the connections between Persia and Sindh, and much like anyone who eats gheeyar or zoolbia for the first time, I won’t be able to stop after just one piece.

I've just seen this! I can't believe you quoted me, I'm so honoured. Love!

What a delicious 😋 read ! 🌹