Following a rice grain trail, from Sindh to Persia

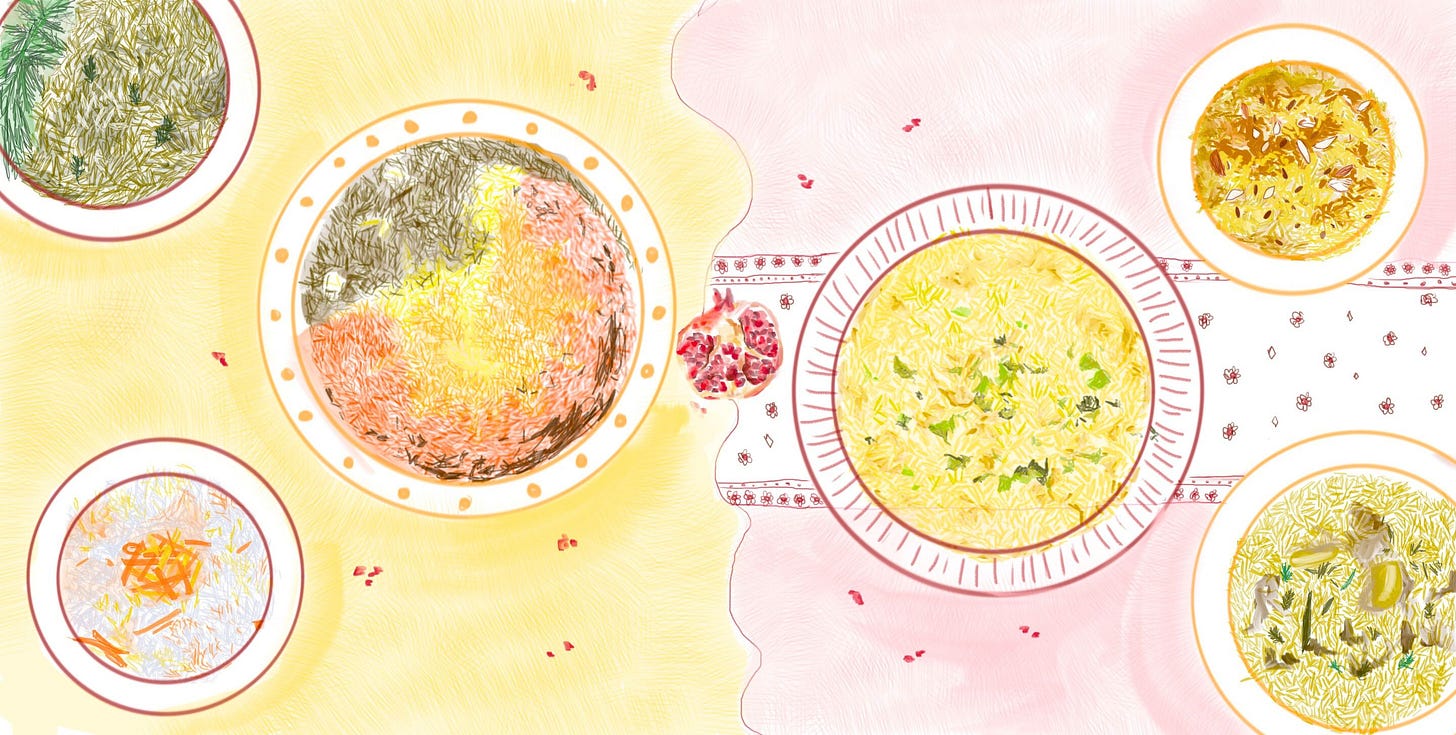

This month, I explore the Persian-Sindhi connection further through rice with a beautiful illustration created by my friend and UX designer, Binoli Shah, further enriching this newsletter.

Until a few months ago, I didn’t know that rice cultivation existed in Sindh. Given that I’m a second-generation Sindhi who has never been to “where I’m really from” (a question that I’m not exempt from, even in India), it is obvious that I’d have no understanding of what crops are cultivated in Sindh. I may not have known that rice was grown in Sindh, however, for as long as I can remember, I have been susceptible to a quiet dissatisfaction if I didn’t eat rice for at least one meal in a day. An affliction that seems almost genetic on my father’s side of the family. This is where I think of the French word manque which is so much more than absentminded missing, it’s a knowledgeable absence of something you know should be there but isn’t. My love for rice is ever present but alas Sindhi rice is nowhere near me. I stumbled on to this realisation as I was trying to prepare a proposal to submit to the Indian Culinary Agenda’s Food Writing prize in February on Sindhi rice. In the process, I not only unearthed the value of rice in Sindhi cuisine but also stumbled onto some even more eery culinary connections between Persia and Sindh. This time, bound together by saffron threads and grains of rice.

In last month’s newsletter, I did a bit of culinary mapping between Persian and Sindhi desserts, all backed up by some pub-quiz worthy historical facts on the introduction of Persian ingredients to Sindh. Now, it turns out that around the time that Persian rule brought spinach, pomegranates, saffron, almonds, pistachios and rosewater to Sindh (and by extension India), rice was in turn introduced to Persia around the same time in 6th century BCE through the Achaemenid empire’s rule in India. Whether this rice originated from India or Southeast Asia is debatable, but the point of introduction nonetheless came through India.

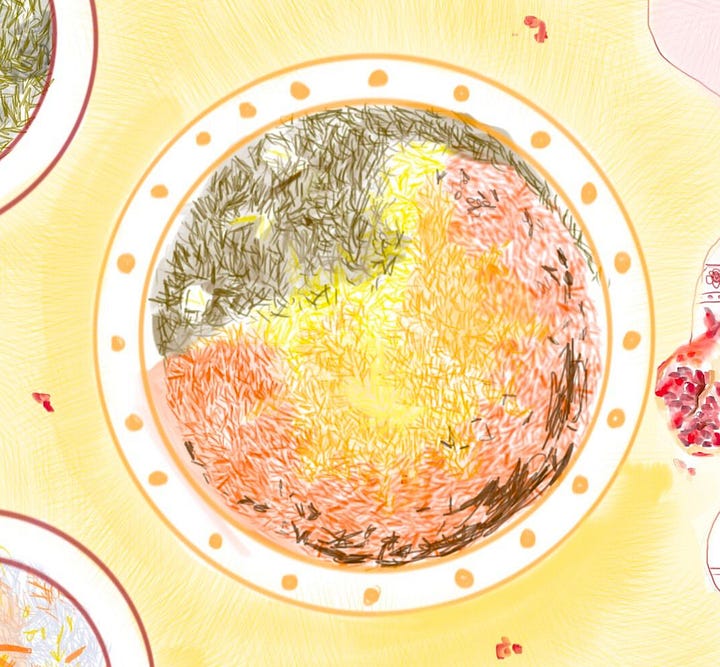

While researching indigenous Sindhi rice varieties grown before partition, I also dived deeper into lesser-known Sindhi rice dishes and serendipitously came across what seems to be their Persian counterparts. Despite being the rice aficionado that I am, even I am incapable of mustering the time to cook three Persian and three Sindhi rice dishes with elaborate photoshoots underway. Which is why I am so incredibly grateful to my close friend and UX designer, Binoli Shah, for illustrating a table full of mouth-watering Persian and Sindhi rice dishes. I can smell the aroma of long grain rice wafting through this array of colours, textures and grains

One of the most underappreciated Sindhi rice dishes is thoomavaro chawar which is a celebration of the arrival of garlic chives every winter in India. The pungent and herby aroma of garlic chives is cooked in a sao masalo, a seasonal greens pesto, with long grain, basmati rice. The delicate scent of freshly cooked basmati rice is almost made zesty with the addition of chives but without completely overpowering l’eau de basmati. During Nowruz, the celebration of Persian new year must accompany a steaming bowl of sabzi polo or steamed herbed rice. The fresh greens like chives, coriander, dill and parsley are emblematic of the renewal of spring and the start of another new year.

This sense of reverence towards seasonal greens extends towards dill as well, in both cuisines. Given the citrusy notes of dill, if used in excess it can easily overpower other herbs within a dish. Where the Persian shivid polow doubles down on the flavours of dill and minced garlic, the Sindhi suvaware chawar combines dill with whole spices that must accompany any Sindhi rice dish: bay leaves, cloves and black peppercorns. Though the preparation of both of these seasonal dishes differs, there still exists a community-wide importance attached to the preparation and consumption of seasonal greens in both cultures. Rice is simply the medium of this celebration.

Sindhi cuisine’s dalliance with saffron and nuts has lasted for millennia since the Persian invasion of 6th century BCE and the proof is also in the sweet rice dish prepared during Sindhi Hindu new year called tairi. What makes tairi unique is that its sweetness is not a result of an excess of sugar or jaggery, something that most Sindhi desserts don’t skimp on, but rather a clever combination of fennel seeds, green cardamom pods, coconut shavings and black raisins. The sharp burst of plump and tart black raisins is balanced by the aniseed flavour of fennel and the almost menthol-like flavour of cardamom, with coconut shavings provided the perfect amount of textural crunch. Tairi is tinged with the canary yellow saffron and inevitably topped with chopped nuts like almonds and pistachios. The Persian shirin polov is extremely similar to tairi in terms of its saffron-infused colour and the slivered almonds and pistachios that adorn this sweet rice dish. Shirin polov has a more bejewelled look by the addition of abundant candied orange segments, grated carrots and ruby-like currants. While most people would assume that a sweet rice preparation would invariably involve some kind of pudding in both cuisines, it is fascinating to see this connection thrive beyond such popular sweet rice dishes.

The interrelatedness between Sindhi rice and Persian rice also becomes more well-defined when we look at the preparation of steamed rice in both cuisines. Whenever I prepared rice for other Indian or even non-Indian friends, there was a look of concern and consternation on my friends’ faces whenever I added salt to a boiling pot of water. It wasn’t until I cooked rice for my friends that I realised that this habit of adding salt to rice is quintessentially Sindhi and perceived as odd by non-Sindhi communities. This realisation was only reinforced after listing to a podcast episode on Sindhi food called Tapestry where two prominent Sindhi authors, Saaz Agarwal and Sapna Ajwani talk about how other Indian communities find our rice-salting habits peculiar and that to Sindhis, rice without salt is simply bland. Upon investigating Persian rice dishes, I found that Sindhis are not alone in their salting habits and that even when making a bog-standard bowl of steamed Persian rice, salt and rice must go hand in hand.

Where Iran still boasts a variety of indigenous Persian varieties of rice, my research into Sindhi rice varieties revealed that our indigenous rice varieties are almost entirely lost. There barely exists one rice variety called sugdasi which is now only cultivated by a handful of Sindhi rice farmers for personal use. Its annual yield is worth nothing more than a couple of kilograms. It’s difficult to talk about recipes without having provenance that comes almost guaranteed with what makes the recipe unique to its community. Maybe there were regional flavour profiles and notes in Sindhi rice varieties that must’ve made Sindhi rice dishes of yore stand apart that much further. Almost like how the soil that coffee beans or grapes are grown in imparts the flavour of the terroir it is grown in. Recipes of a displaced diaspora then cease to become an extension of the terroir and rather a blueprint for its preservation.

I found it amusing that a lot of the Persian food blogs run by Persian Americans now living in the United States urge their readers to seek out Indian or Pakistani basmati rice if they’re unable to find Iranian rice varieties in their local corner shops. I suppose that’s what I and millions of other Sindhis in India have been doing, seeking Indian basmati rice because we are not likely to ever find Sindhi rice in our corner shops due to an imposed geo-political border. Regardless of the future of Sindhi rice, I think it is worth acknowledging the various invisible strings between rice preparation in Sindhi and Persian communities. If only to strengthen our collective understanding of what Sindhi cuisine is all about and the forces that influenced it.

What a fun read. But I must say I find similarities like this between most Persian dishes and Indian dishes.